- Turkish-style Baklavas are selling like hotcakes

- Metropolitan Museum of Art Exhibition: 500 Years of Western Painting

- Full capacity events to return soon but no loud voices please says Japan

- Editor’s Pick: The Best of Tokyo’s winter illumination events

- Tokyo’s Fun ice skating rinks return for the season

- American Thanksgiving meals 2021, Tokyo style

- Christmas Market at the Yokohama Red Brick Warehouse returns

- Roppongi Hills Christmas Market

- Upcoming VenusFort farewell events before it closes down for good.

- November NO-admission-fee days at the Snoopy Museum

-

Godiva has a new chocolate-coated potato chips

What can be more addictive to snack on while watching your favorite Netflix film than a...

-

Louis Vuitton’s “Volt” line releases elegant unisex bracelets

A charming collection of unisex fine bracelets created by Louis Vuitton’s artistic director for watches and...

-

Is it worth buying the new 5-G-compatible Balmuda android?

Today, Balmuda Technologies, a new division created by Japanese company Balmuda,a cult brand for electric home...

-

Subaru’s first electric SUV is a looker!

Subaru’s first new SUV car named Solterra EV is coming to car showrooms in Japan, Europe,...

-

Tokyo’s Fun ice skating rinks return for the season

The ice rinks around town return and it’s time to have fun. Here are some of...

-

Budget-friendly and stylish winter clothing for children

Yuki Owada, a kids fashion stylist has abundant styling suggestions for children of all ages that...

-

Hanuri Korean restaurant opens in Shibuya

The fascination for Asian cuisine may have started by food vloggers and chefs but Instagram has...

-

Retailers announce price increases: What will affect the family’s purse strings?

Perhaps by now, you have spotted that the price of a product/service you paid for a...

-

The fuss-free way to make French Crêpes at home.

Perhaps the reason the most important meal of the day is also the most neglected is...

-

Sony releases a headset with a wide viewing angle for use with Xperia 1 II smartphone

Sony is rolling out Xperia View, a new virtual reality (VR) headset for use with the...

-

This place serves Mexican burgers and all-you-can-eat fries for lunch.

Tucked in the narrow business streets of Shiba, Minato ward, is a Cancun-style taqueria that Mexican-starved...

-

Grand Central Oyster Bar offers the best of the fall season.

Modeled after one of New York city’s most spectacular restaurants with its famous vaulted ceilings, there...

-

The Tokyo Sky Tree is Ready for Christmas

When the famous Tokyo Sky Tree illumination wraps Asakusa in festive twinkling green and red lights,...

-

Kimono and Athleisure. Do they go together?

The kimono is undergoing a major evolution in Japan. Many traditionally hand-woven fabrics used for kimono...

-

The Ashikaga Flower Park Opens for the flower-viewing season

If you’re aching for some autumn fix, then we recommend you to round up the kids,...

-

Japan eyewear brand releases rose-tinted lenses

Rose-tinted lenses are not just a great way of blocking blue light or reducing eye strain....

-

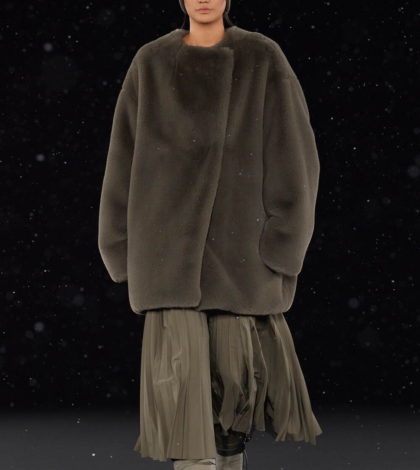

Moncler-Hyke Fall Winter Collaboration: Simple and Elegant

Simple and minimalist Japanese cult brand Hyke in collaboration with Moncler Genius unveils a utiliarian style...

-

Shimokitazawa’s Curry Festival Is Back and Bigger Than Ever

After a two-year hiatus, Shimokitazawa Curry Festival 2021 is back for its 10th anniversary. Around 124...

-

Michelin-starred Sushi train restaurant opens in Omotesando

Ginza Onodera, a Michelin-starred restaurant known for sushi and tempura will introduce a new sushi train...

-

The Prince Park Tower Tokyo & The Tokyo Prince Hotel are now taking orders for Santa-inspired cakes.

Order-made cakes in Tokyo are definitely a bit pricier than buying from Costco but splurging on...

Babies

-

The stroller made for Tokyo’s tight and narrow spaces.

Hopping on and off busy trains in Tokyo with kids in tow...

Buzzworthy

-

Mozzarella cheese overtakes Camembert’s popularity in France

For the first time in cheese-loving France, sales from Camembert continues to decline by...

- November 6, 2021

- 0

Dining Out

-

This place serves Mexican burgers and all-you-can-eat fries for lunch.

This place serves Mexican burgers and all-you-can-eat fries for lunch.

Tucked in the narrow business streets of Shiba, Minato ward,...

- October 25, 2021

- 0

-

Grand Central Oyster Bar offers the best of the fall season.

Grand Central Oyster Bar offers the best of the fall season.

Modeled after one of New York city’s most spectacular restaurants...

- October 20, 2021

- 0

Cooking Good

-

It tastes very close to KFC chicken.

It tastes very close to KFC chicken.

I know many of you will think it’s weird but...

- December 22, 2021

- 0

-

Garlicky, Creamy Shrimp Kids Will Love

Garlicky, Creamy Shrimp Kids Will Love

This simple yet easy-to- cook meal makes for an appetizing...

- November 9, 2021

- 0

Parenting

-

Antibodies in Breastmilk of Moms Who’ve Had COVID Can Protect Babies, says new study.

A new study suggests breastfeeding after COVID-19 infection may increase...

- November 24, 2021

- 0

-

Bedtime fail: Daughter interrupts the prime minister of New Zealand’s at-home livestream

New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern was livestreaming about important...

- November 10, 2021

- 0

Tokyo Lifestyle

-

Louis Vuitton’s “Volt” line releases elegant unisex bracelets

A charming collection of unisex fine bracelets created by Louis Vuitton’s artistic director for...

- January 28, 2022

- 0

-

Pykes Peak releases its X20 foldable ebike

On November 18, the electrically assisted Pykes Peak bicycle X20 will be on sale....

- November 9, 2021

- 0

-

Budget-friendly and stylish winter clothing for children

Yuki Owada, a kids fashion stylist has abundant styling suggestions for children of all...

- November 2, 2021

- 0

-

Japan eyewear brand releases rose-tinted lenses

Rose-tinted lenses are not just a great way of blocking blue light or reducing...

- October 14, 2021

- 0

Holiday Food

-

Special dinner offering at Kimpton Shinjuku Tokyo

Special dinner offering at Kimpton Shinjuku Tokyo

The District Brasserie Bar Lounge at luxury boutique hotel Kimpton...

- December 22, 2021

- 0

-

American Thanksgiving meals 2021, Tokyo style

American Thanksgiving meals 2021, Tokyo style

November 25th is American Thanksgiving Day. Thanksgiving, being a...

- November 7, 2021

- 0

In Focus

Community

-

Half of Japan’s Job Burnout-related suicides happened within 6 days after the onset of depression symptoms

Japan reported that 497 suicides between 2012 and 2017 were karojisatsu or job burnout-related....

- October 26, 2021

- 0

News

-

Pfizer or Moderna: Which booster shot is more effective against Omicron?

The discovery of the Omicron variant in Nov 2021 raised...

- February 2, 2022

- 0

-

Tokyo’s new coronavirus caseloads hit all-time high level

The number of new coronavirus cases reported in Tokyo on...

- January 28, 2022

- 0

-

Quarantine to be shortened from 10 to 7 Days for close contacts

Japan’s health ministry is considering shortening the quarantine period for...

- January 28, 2022

- 0

-

Bigger power bills will be arriving soon.

Did you notice that your electricity bill this year is...

- December 27, 2021

- 0

-

200 Public School Teachers in Japan Punished for Sexual Abuse

Japan’s education ministry revealed on Tuesday that a total of...

- December 22, 2021

- 0

-

Antibodies in Breastmilk of Moms Who’ve Had COVID Can Protect Babies, says new study.

A new study suggests breastfeeding after COVID-19 infection may increase...

- November 24, 2021

- 0

-

Australia reopens borders to travelers from Japan starting next month

The Australian government said Monday it will relax border restrictions...

- November 22, 2021

- 0

-

JR Tokai Line gives free bullet train rides to kids

JR Tokai lines announced today children under the age of...

- November 19, 2021

- 0

-

New D-I-Y Apple repair program starts next year

Starting next year, iPhone users will be able to carry...

- November 18, 2021

- 0

-

Look to 2022 lucky bags for workation opportunities.

The object of New Year shopping tradition in Japan...

- November 16, 2021

- 0

-

Japan-approved booster program starts next month.

Yesterday, Japan’s health ministry decided that the third shot of...

- November 16, 2021

- 0

-

Turkish-style Baklavas are selling like hotcakes

Have you ever taken a bite of Baklava and felt...

- November 16, 2021

- 0

-

Full capacity events to return soon but no loud voices please says Japan

There are talks the Japanese government is planning to relax...

- November 13, 2021

- 0

-

Japan makes one terrific electric bike for you and your pet

When it comes to having a fun activity with pets,...

- November 13, 2021

- 0

-

Vintage Apple computer built by Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak auctioned off for US$400,000.

A student who chooses to remain anonymous has kept an...

- November 11, 2021

- 0

-

Japan approves the use of Pfizer booster shots only to people 18 and above.

Yesterday, Japan’s health ministry panel approved the use of Pfizer...

- November 11, 2021

- 0

Family health

-

Study: Omicron survives longer on plastic, skin, than earlier coronavirus variants

A study conducted by the researchers from the Kyoto...

- January 26, 2022

- 0

-

Antibodies in Breastmilk of Moms Who’ve Had COVID Can Protect Babies, says new study.

A new study suggests breastfeeding after COVID-19 infection may...

- November 24, 2021

- 0

Exciting Things To Do

-

Feeling burnt out? Get an hour of tranquility with an intriguing animal by your side.

Coping with pandemic stress? Visiting an owl café in...

- November 17, 2021

- 0

-

Metropolitan Museum of Art Exhibition: 500 Years of Western Painting

Travel back in time as a family to see...

- November 15, 2021

- 0

-

NamjaTown and its weird ice cream flavors

We visited Fukuburo Dessert Yokocho, one of two food...

- November 15, 2021

- 0

Coming Soon: Movies

-

“The Boss Baby - Family Business” in Tokyo theatres Dec. 17

When American computer-animated comedy film - The Boss Baby...

- November 7, 2021

- 0

Escape

-

Editor’s Pick: The Best of Tokyo’s winter illumination events

Everyone who lives in Japan knows festive lights are...

- November 8, 2021

- 0

-

The magical autumn colours of the Japanese Alps offer respite during pandemic.

As the most eye-catching red and purple pigments of...

- November 7, 2021

- 0

Education

-

200 Public School Teachers in Japan Punished for Sexual Abuse

Japan’s education ministry revealed on Tuesday that a total...

- December 22, 2021

- 0

-

Why century-old Montessori approach remains relevant today.

The influence of home as children’s first school where...

- November 9, 2021

- 0

Family Finances

-

Bigger power bills will be arriving soon.

Did you notice that your electricity bill this year...

- December 27, 2021

- 0

-

When do Japan homeowners pay property taxes?

A property tax is levied on homeowners regardless of...

- November 15, 2021

- 0

-

Lawson releases 100-yen meatball lunch packs

A typical Japanese bento sold at convenience stores come...

- November 9, 2021

- 0

Tech

-

New D-I-Y Apple repair program starts next year

Starting next year, iPhone users will be able to...

- November 18, 2021

- 0

-

Is it worth buying the new 5-G-compatible Balmuda android?

Today, Balmuda Technologies, a new division created by Japanese...

- November 17, 2021

- 0

-

Travel

-

Tech

- Is it worth buying the new 5-G-compatible Balmuda android?

- Vintage Apple computer built by Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak auctioned off for US$400,000.

- Sony releases a headset with a wide viewing angle for use with Xperia 1 II smartphone

- Newly launched Nintendo Switch OLED in resale sites at a higher price

-

Homebase

-

Culture

-

Health

-

Celebrity Interview